Sustainable Travel Meets Bedouin Tradition at This Remote Hotel in Jordan

Conservation and cultural exchange in the Jordanian wilderness

When you think of Jordan, you probably think of Petra, the red-hued ruins of an ancient city so breathtaking they’re considered one of the Seven Wonders of the World. But Feynan Ecolodge, located about two hours from Petra in eastern Jordan’s Wadi Feynan, is another wonder worthy of a visit.

The quiet hits you on arrival. After you check in at reception, you’re still a bouncy half-hour drive away from the main building, trading out your own transportation to hop into a 4x4 trunk that's better equipped to handle the rough roads through the Dana Biosphere Reserve. While you've surely passed a few small communities (and a few intense games of youth football) on your way to Feynan, the area directly surrounding the lodge is populated by only a handful of Bedouin communities. It’s a place where you can watch the rugged hills of the Great Rift Valley turn pink in the evening light, with only an occasional local and their herds of goats for company.

In short, as I realized upon stumbling out of the 4x4 after the bumpy ride, you’re really out there.

The Dana Biosphere Reserve covers 320 square kilometers of land, and is home to some of Jordan’s most diverse nature, including around 700 different plant species and over 250 animal species. Perhaps this is why it’s hard to shake the feeling that Feynan’s setting isn’t meant to be disturbed. But this feeling is what inspired the ecolodge in the first place.

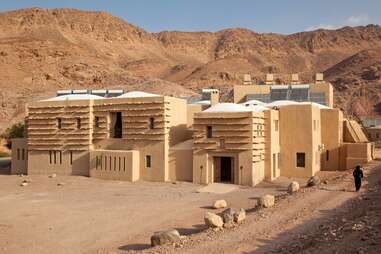

Built in 2005 by the Royal Society for the Conservation of Nature (now under the management of EcoHotels), Feynan is Jordan’s first ecolodge, created with the hopes of opening up the region to outside visitors while providing locals with an alternative source of income. Every element of the hotel is designed in accordance with those twin ideas of cultural exchange and environmental care.

Inspired by caravan culture, each of Feynan’s 26 guest rooms is arranged around a large open courtyard, where instead of camels (as it would have been back in the era of trading posts), guests congregate into the evening. The building’s design (including the stone slabs near the entrance) allows for naturally controlled heating and cooling. And while elements like drinking water delivered in oversized clay pots point to reducing the lodge’s environmental footprint, almost everything you give up in the name of ecology simply adds to the experience and ambiance.

No electricity after dark other than solar-power overhead lamps in ensuite bathrooms? Let me introduce you to the mood-setting power of candlelight, both in public areas and guest rooms. In the rooms, mirror-lined shelves amplify flickers of light, something no lamp could replicate. Miss the meat at dinner? No, you didn’t, thanks to the power of Feynan’s Arabic buffet, featuring falafel, cheese, locally baked bread, vegetables, and dips like hummus and mouttabal. (Note: In alignment with the region’s Muslim beliefs, no alcohol is served—but if you must have a tipple, booze is allowed on a BYOB-basis, provided you remain discreet.) Wi-Fi is limited to the charging station by the front desk, but even as a millennial with an attachment to both work and memes, I found the restriction strangely comforting.

But perhaps the most incredible part of the Feynan Ecolodge experience is the activities that put you in direct contact with the local community. You can sign up for cooking classes, hikes, and even shadow nearby goat headers, for only a small additional supplementary fee (usually about 4 JOD, or less than $6 US), a sum that goes directly to guides and families. Activities I enjoyed included a guided stargazing experience on the roof of the lodge, which takes advantage of the area’s lack of light pollution and subsequent incredible view of the night sky. As the guide set up telescopes and traced the constellations with a laser pointer, one of the local cats crawled into my lap and began to purr. I also visited a Bedouin tent for tea, which while a transactional visit, was fully suffused with the spirit of hospitality.

As I sat with my hosts, I learned that about 80 families (around 400 people) make their homes in this area, and that they are one of the last remaining Bedouin tribes who have maintained their traditions in the face of change.

As is customary, families relocate to a different location in the summers, following the same paths and pitching their tents in the same areas each year (minus any family members who must now spend the end of the school term near the school). Coffee is still purchased green, then roasted and sipped from a communal cup. Kohl eyeliner is still created through burning cotton and olive oil, and applied with a small stick.

The mission behind Feynan Ecolodge fits into the local traditions nicely, too. As a Bedouin member of staff told me, taking care of the Earth and friends—whether new or old—is considered a blessing. By the end of my visit, I’d experienced plenty of both.