Bathe in the Glow of Las Vegas' Past at the Neon Museum

In a city that likes to blow up its history, the museum preserves its most brilliant parts.

Betty Willis should’ve gone for the cash. In 1959, the pioneering female commercial artist designed what is probably the most famous—and one of the longest lasting—neon symbols in the world. In 1952 she was employed by Western Neon Sign Company when a salesman named Todd Rogich, seeing welcome signs proliferate in other locales, approached her about designing a fitting emblem for the city. He suggested Las Vegas’ reflect its flashy veneer by utilizing neon lighting: one of the city's most familiar, yet somehow still novel, features.

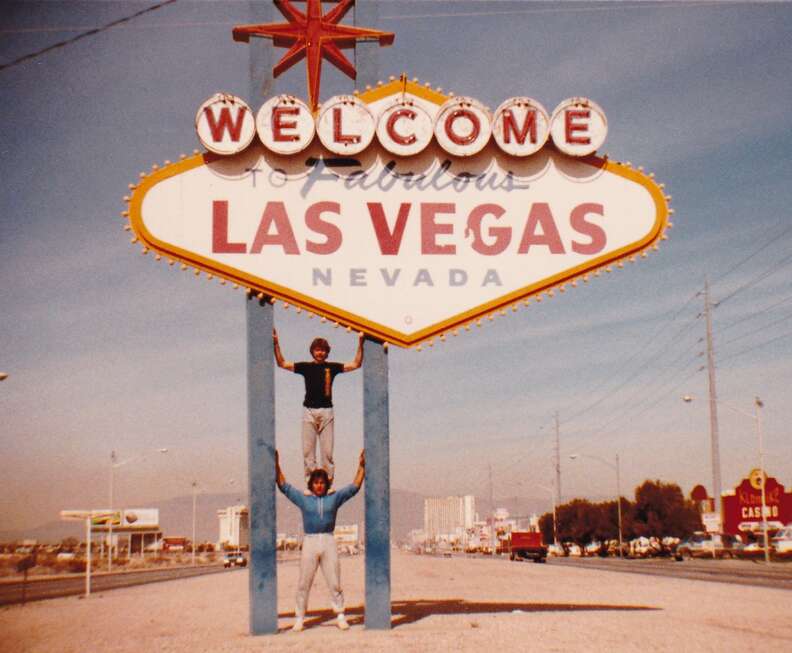

Now recognized the world over, Willis's 25-foot Welcome to Fabulous Las Vegas sign sits on the southern tip of the Strip—technically in unincorporated Clark County—flanked by palm trees and Elvis impersonators, roadside Americana beckoning to motorists with its promise of possibility. Balancing on two poles, an exaggerated Googie-style diamond is bordered with flashing incandescent bulbs.

Red letters spell out “WELCOME” against silver dollar coins rimmed in white neon, a nod to both the Silver State and the gamblers attracted to it. And on the top sits a red metal starburst outlined in brilliant yellow. Willis told the New York Times before her death in 2018, “I added a Disney star for happiness.” In 2008 the city constructed a parking lot for the sole purpose of encouraging pedestrians to line up for a perfect (and free) photo op. The sign cemented Willis's legacy, thanks to its alluring glow.

Neon captivated from its very inception. In 1898, British scientists William Ramsay and his assistant Morris Travers discovered the new element, which emitted a magical crimson glow when electrically stimulated. To say they were in awe of the element’s power would be an understatement: of the discovery Travers wrote, "the blaze of crimson light from the tube told its own story and was a sight to dwell upon and never forget."

The first neon signs were unveiled in Paris in 1910, and it didn’t take long for the illuminated phenomena to make its way to the States, rising in tandem with the country’s romance with automobiles. It’s said the United States’ first neon sign was erected in 1923 in Los Angeles. It sat atop a hotel reading “Packard” in four-foot-high red and blue lettering, and drew onlookers from far and wide, creating traffic jams with its eminence.

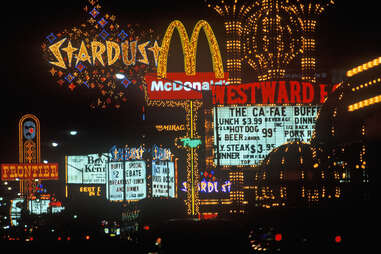

But it was Vegas that fully understood—and utilized—neon’s true potential. In the early 1930s, after the legalization of gambling brought an influx of tourists and the construction of the Hoover Dam an abundance of electricity, Las Vegas transformed from a sleepy frontier town to one dripping with gaseous, colorful glitz. The downtown thoroughfare of Fremont Street earned the nickname of Glitter Gulch in the 1940s, with everything from pharmacies to casinos lit up in lights.

Rogich eventually sold the Welcome to Fabulous Las Vegas sign to Clark County officials for $4,000, and as the story goes, Willis declined to copyright the design, saying it was her gift to her beloved city. But she failed to remember that her city was built on capitalism—and opportunity. Years later, after seeing the sign replicated everywhere from snow globes to boxer shorts to potato chips, she acknowledged, “I should make a buck out of it. Everybody else is.”

Today, you can see the Willis's sign whenever the mood strikes. In 2013, solar panels were attached, ensuring the symbol’s longevity and making it much more energy-efficient (not quite in line with the rest of Vegas, but a hope for the future). Listed in the State Register of Historic Places, it’s an unusually enduring marquee in a city whose M.O. is to repeatedly pave over its past.

Many of Vegas’ other once-iconic neon signs are forever gone, smashed into shimmering shards and committed only to memories of the city’s mid-century opulence. But if catching sight of Willis’ glowing contribution sparks an interest in the element's reaches, you can always get your fix at the Neon Museum.

A ticket to an illuminating history

In the early 1990s, Las Vegas began making room for new hotels the best way they knew how: by imploding the old ones in splashy, theatrical affairs. Sometimes they had accompanying fireworks, one time they had pirates. The Dunes was the first to meet this fate back in 1993 (making way for the Bellagio), followed by the Landmark in 1995, a space needle-like structure whose crumbling implosion was captured in the Tim Burton film Mars Attacks. Then, like dominoes, the Sands was eliminated in November of 1996, and the Hacienda went a month later. The latter's booming demise was showcased as part of a televised New Year’s Eve extravaganza that year.

In 2007 came two more major demolitions: New Frontier, a western-themed Howard Hughes joint where both Sigfried & Roy and Elvis made their Vegas debuts. And the Stardust Casino, inspired by a mid-century affinity for space exploration, frequented by the likes of Sinatra, and once the domain of kingpin and bookie Lefty Rosenthal, AKA the inspiration behind the Hollywood blockbuster Casino.

The artists who labored over the neon signage marking these disappearing artifacts despaired before resolving to save their works. Rescuing the jagged and otherworldly—not to mention massive—Stardust sign was an especially significant feat: The letters range from 14 to 18 feet in height and contain over 1,100 light bulbs, 975 in the S alone. Imposing in stature, it probably can’t be seen from space, but it sure gives the impression it could.

Today, however, it can be seen in the Neon Museum. Established in 1996 as a nonprofit to collect, preserve, and exhibit discarded neon signs, the museum began with a donation by the Young Electric Sign Company and was initially only let in visitors by appointment. In 2012, the campus’ “boneyard”—the space where items no longer in use are stored—opened to the public.

Approximately 250 signs populate the museum, some dating back to the 1930s, a number always growing as more are donated (the only way they acquire signs). Around two dozen of those are electrified, providing viewers with a dazzling taste of old Las Vegas. And in true Vegas fashion, you can even have your wedding there, surrounded by radiance.

Like much of Las Vegas, the open-air (or closed, when it’s raining) Neon Museum is best experienced in full illumination after the sun goes down. But swinging by in the daytime—even if it’s closed—can still prove fruitful. There’s a mural on the outer wall of the North gallery painted with the greatly influential yet not-so-well-known figures that shaped Las Vegas history, including, of course, welcome sign mastermind Betty Willis.

And things get especially interesting if you’re an architecture buff. The striking shell-shaped entrance that serves as the museum’s Visitors Center once belonged to the La Concha Motel, which operated on the Strip from 1961 to 2004 and was famously patronized by slick celebrities and Hollywood types. But, more importantly, it was designed by trailblazing African American architect Paul Revere Williams, who, in 1923, became the first Black architect to join the American Institute of Architects. The prolific pioneer designed upwards of 2500 buildings, including works for Lucy and Desi Arnaz and Carey Grant. (In a tragic, infuriating, sad, and loathsome twist, he’s also known for teaching himself to draw upside down so white clients wouldn't be uncomfortable sitting next to him.)

Most of Williams’ creations were in his hometown of Los Angeles, but there are others scattered around the country. Like the St. Jude Children's Hospital in Memphis, which he designed for free, and the La Concha, whose lobby was saved from demolition in 2005 and relocated to the Neon Museum shortly thereafter.

Arrive at the museum at nightfall and the La Concha shells buzz, getting lit alongside its neon cohort. But before you anywhere near the museum’s entrance, you’ll spot one of its most recent—and most gigantic—acquisitions: the 82-foot-tall Hard Rock Café guitar shooting straight up from the boneyard, a celestial instrument seemingly floating in mid-air.

The first of its kind, the hulking instrument spent 1990 to 2017 on the corner of Paradise Road and Harmon Avenue in Vegas, and even made it to the silver screen with appearances in classics like Honey I Shrunk the Kids and National Lampoon’s Vegas Vacation. With 1,530 incandescent bulbs and around 4,110 feet of neon tubing, it took 1,650 hours and $250,000 in crowdsourced funds to restore. (All that, and it can’t even play a tune.)

Enthusiastic museum guides offer tours, detailing backgrounds stagnant plaques could never deliver. Each turn captures a specific time and place in Las Vegas’ complicated and storied history.

Take another of Betty Willis’s works: the Moulin Rouge sign, propped up near the entrance and spelled out in swooping pink cursive. Named after the Parisian club, it marked the first desegregated hotel casino in town. It hit the Strip in 1955, and while its tenure only lasted a brief six months, its impact is immeasurable.

The Moulin Rouge relic is right across from Binion’s Horseshoe. Owned by career gambler and racketeer Benny Binion, the property was Glitter Gulch personified. Boasting a personal history as scandal-prone as his industry, Binion was known for both a murder conviction and, on a lighter note, initiating the custom that players drink for free. (Thanks, Benny.)

A little further down, visitors will stumble upon the sign for the Sahara Hotel, famous for once hosting the Beatles overnight (the band was originally scheduled to play a show there, too, but it had to be moved when checking into the hotel spurred such a commotion). Elsewhere, there are examples of the first moving signs alongside non-neon attractions like a gigantic skull salvaged from Treasure Island, staring up into the night sky.

Across the way, the North Gallery houses Brilliant!, an audiovisual presentation that begins with a demonstration of how neon works by agitating gas in a tube before reanimating 40 different signs using projection mapping. There are three shows every evening.

And if you feel like going all out, you can even make a neon night of it by booking a helicopter tour package. The choppers first swoop you over the current-day Strip, before the tour deposits you at the Neon Museum, juxtaposing the present day with where it all began.

To forecast Vegas’ future, just look to its past

Downtown is a fitting home for the Neon Museum: While the Strip reinvents itself every other day, Vegas’ less-touristy area strives to look to the future while preserving the past. Here, you can still get a sense of what drove people to forge this thriving, anything-goes town in the middle of the Mojave Desert. In 1905, the city was born by auction, and Fremont Street became its glittery nexus. Today, the attraction stands as the covered Fremont Street Experience, complete with a nightly light show and the SlotZilla zipline zooming past retro landmarks like the Golden Gate Hotel Casino, opened in 1906, 1946’s Golden Nugget, and the Four Queens, dating to 1966.

In the Four Queens, you’ll find Hugo’s Cellar, opened in 1973 and known for one of the best throwback steakhouse deals in town. Expect tuxedo-clad waiters and a tableside salad cart and, if you’re a lady, they’ll greet you with a (surprisingly long-lasting) rose.

The El Cortez Hotel, once owned by notorious gangster Bugsy Siegel, still looks much like it did when it opened in 1941 as downtown’s first major casino resort. Read up on this property as well as the rest of the city’s underworld past in the nearby Mob Museum, an almost immersive experience, as it's housed in the former courthouse where the infamous Kefauver trials were held in the early 1950s. It was there that the sordid bond between casino owners and organized crime bosses came to light.

Downtown also strives to revitalize its landscape with spots like the D Hotel, opened in 2012 and incorporating vintage touches like flair bartenders and old-school slot machines in its second-floor casino. The Lip Smacking Foodie Tour gives a good overview of the changes, merging the area’s history with its modern progress by taking you past new murals and into contemporary restaurants like Carson Kitchen, founded by celebrity chef Kerry Simon, and Container Park, where a sea of shipping containers have been turned into bustling food stands.

Look at any old picture of Fremont Street and you’ll spot a 40-foot-tall neon cowboy in front of the Pioneer Club, seemingly pointing at himself. That’s Vegas Vic, erected in 1951. At one point, he waved and exclaimed “Howdy, Partner!” every 15 minutes. He’s still there, though his voice box has since been silenced.

But if you’re looking for Vegas Vic’s long-lost girlfriend Vegas Vickie—onetime fixture of the Glitter Gulch—you’ll find her fully restored and kicking up her heels at the new Circa Resort & Casino right on the Fremont Street Experience, where she has her own cocktail lounge. Opened in 2020, Circa is a destination in itself, with its three-story Sportsbook (the largest in the world) and Stadium Swim—a pretty ingenious setup where you can splash around in six pools on three different levels while watching multiple sports on soaring television screens.

Circa just so happens to occupy the same location as the Northern Club, the first casino in Nevada to get a gambling license. These days, the venture is hoping to do the same thing for Downtown that the Northern Club did for, well, the entire world: Light it up like never before.